On Farmers’ Seed Systems (FSSs) sdf

Nayakrishi Andolon || Saturday 04 March 2023 ||

Nayakrishi Andolon || Saturday 04 March 2023 ||

The Farmers' Seed Systems (FSSs) are by far the most important source of seed in most countries and play a vital role in countries like Bangladesh. Therefore FSSs deserve close and critical attention by policy makers. There are misguided and ill-conceived efforts to replace the FSSs for a system in which seeds are treated as dead ‘inputs’ and farmers are compelled to buy seeds from commercial markets. Separation of seeds from their organic relation to farming and FSSs distorts the agroecological role of farming households. Such disarticulation results in treating biological wealth of a community as ‘common heritage’, i.e., rendering seeds as raw materials for exploitation and commodification. It denies the truth that seeds and biological resources belong to particular and specific communities living in an agroecological system. Seeds are held in common as community property. Rhetoric mystifies the concrete reality and opens up scopes to steal living materials that rightfully belong to farming communities. Like colonization of land, colonization of the biological world and biopiracy of seeds become the norm of the industrial world. . Seeds are stolen, privatized and resold. The corporate piracy of the most valuable articles of farming households is justified through various patent and seed laws.

This is the industrial-ideological context where it is mighty difficult to argue for the irreplaceable role of FSSs to ensure seed and food sovereignty. Nevertheless, the major part of agricultural land in the world is still sown with seed that is informally produced by farmers. Corporate attempts to desperately create a so-called ‘formal seed sector’ that supplies 100% of the seed for planting is unrealistic and dangerous. More so for a country like Bangladesh in the context of constant natural calamities and climatic disasters. Farmers have always been the innovators of flood and drought-prone varieties or varieties that contribute to the resilience of their diverse systems to cope with nature. Marginalizing the FSSs in agriculture, science and technology policies and denying the role of small farming households in research and knowledge practice is wrong. It is utterly inconsistent with the goals of sustainability. The importance of FSSs merits closer attention at the policy level and in technical assistance projects to accelerate the process of quality seed production and seed exchange. Linking formal and FSSs and integrating both into comprehensive national seed policies is the order of the day. It is utterly a wrong strategy to build infrastructure and investment climate for the formal (private and public) seed sector that could hardly contribute to the ground realities of seeds and agro-ecological concerns. Singular direction to create commercial and corporate seed markets ignoring the necessity to build up a strong biological and agro-ecological foundation of agriculture could be disastrous for seed and food sovereignty of Bangladesh, specially when the country is aiming graduation from its current economic status to the status of a developing country.

Ideology, vocabulary and rhetoric

The ideology of corporate and industrial agriculture has long treated seeds as mere dead inputs for industrial production. This perspective denies the intrinsic nature of seeds as living beings with the power to regenerate themselves naturally. Instead, it replaces the agency of nature with the agency of corporations, reducing natural biological processes into capitalist processes. As a result, seeds are treated as raw materials that can only be used once, forcing farming communities to buy new seeds from seed corporations. This is also the reason why corporate ideology claims farmer seed as inefficient and uses corporate parameters to prove that FSSs lack the ability to ensure seed quality control and crop variety maintenance. Corporate ideology thus equally justify the historic scandal of biopiracy: the stealing of farmers’ seed and collecting them in genebanks and seed vaults.

The agroecological principle recognizes seeds as living beings that carry within them all the natural processes necessary for regeneration. Therefore, it is crucial to avoid discussing seeds as mere industrial inputs or "factors of production." Farmers, as stewards of the land, are the only ones who can facilitate natural processes and ensure the continuation of ecological cycles. Farmers' agency is inseparable from the natural ecological processes, and they are not simply "managers" of seed-keeping, but integral to the concept of agroecology.

The corporate world typically ascribes seed quality to a limited set of parameters and therefore inherently weak in meeting the challenge of local conditions. Corporate ideology of standard parameters presupposes homogeneous production conditions and accordingly seeds come in packaged bundles that require extraction of groundwater for irrigation, use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, ets. The so-called standard parameters are a hoax to destroy local agro-ecological conditions. The standard parameters are replaced with elements that could be commodified and sold for profits.

Seeds by definition exist as potential traits that are expressed only in definite biogeographical and ecological conditions and therefore can not be reduced into calculative parameters. Only farming communities through community knowledge, tradition and memory know where and how the potential traits of seeds are expressed. Farmers’ knowledge of local conditions is critical to meet the climatic variability and uncertainties of nature.

Seeds are essential to the regeneration of individual and community life. They are the practical and sensuous aspect of the natural process, articulated through local language, indigenous discourses, and knowledge practices. Seeds and associated local and indigenous knowledge systems mediate community relations and form larger ecological landscapes such as villages, countries, or rural spaces. They are encapsulated in community relations and are often inscribed in local or indigenous names.

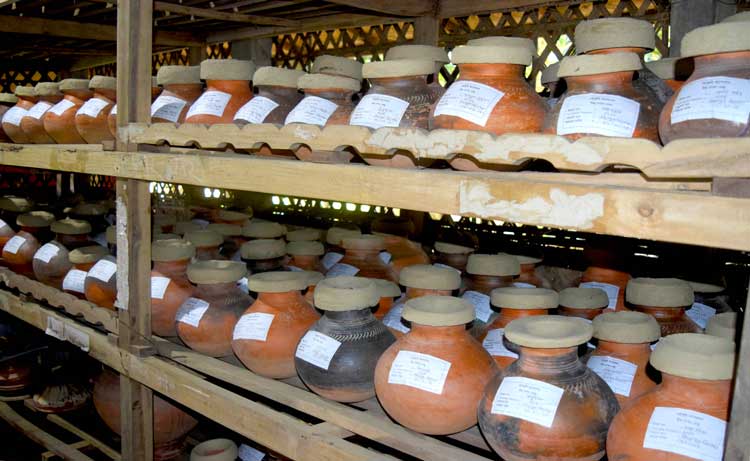

Seeds are the key through which farming communities play a fundamental agro-ecological role by planning and designing landscapes defined by agro-biological diversity and discouraging monoculture. By resisting monoculture, Farmers' Seed Systems also resist the commodification of seeds and life forms. The corporate industry can thrive on monoculture and is keen to destroy biodiversity to transform them into ‘raw materials’ of production. Farmers' seed systems conserve, manage and regenerate diverse species and varieties and can ensure the flow of various natural and ecological cycles. The farming households function both as in-situ and ex-situ conservation of seed and genetic resources and contribute to regenerating the biological foundation of rural communities as a whole.

Because of the long and arduous movements, policymakers, development practitioners, and researchers now acknowledge the importance of agrobiodiversity and germplasm conservation in food and nutritional security as well as agricultural development, and rural livelihoods, but fail to see the role farmer’s seed systems play in this regard. The corporate commercial seed system that is based on monoculture and commodification of life is the major threat to agrobiodiversity and rural livelihood. The importance of the farmers’ seed system, therefore, has hardly been recognized from this perspective. It is important to reiterate that the farmer seed system can function only through farmers' formal and informal networks and is destroyed by the commercial exchange of seeds and genetic resources. Farmers' seed systems are more efficient in the dissemination of seeds and agroecological knowledge.

It is therefore imperative to recognize the importance of FSSs as integral to ecology and biodiversity. The concept of FSS is inbuilt within the notion of agroecology and they never had never been disarticulated except in capitalist-industrial era. We must always remain alert to the vocabulary and rhetoric of corporations. Farming communities are the stewards of the land and have an essential role to play in ensuring the continuation of ecological processes. We must prioritize the preservation of local and indigenous knowledge systems to promote the wider application of traditional practices and ensure the equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization.

The Convention on Biological Diversity recognizes the role of FSSs, emphasizing the importance of respecting, preserving, and maintaining the knowledge, innovations, and practices of indigenous and local communities that embody traditional lifestyles. It also promotes the wider application of such knowledge, innovations, and practices with the approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge and encourages the equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization. (CBD 1992).

The resilience of agriculture and the ability of the farming community to counter the variability of climate change and disasters caused by natural calamities are squarely related to FSS. It is the farming communities that have historically invented seeds that can stand drought, salinity, flood, etc. The FSSs mean resilience and modern varieties are often unsuitable to meet disastrous natural calamities. Resilient seeds maintained by farming households are always ongoing experiments and evolve through local use in local conditions. Resilient seeds discovered, invented, and maintained by FSSs can not be replaced by corporate-sponsored ‘smart’ agriculture or ‘smart’ seeds.

Like seeds, the FSSs is also a living system that changes and grows with the local environment and agroecological conditions. Food systems are also an integral part of the FSSs, constituting resilient culture, traditions, and lifestyles bearing all the signatures of agroecology.

Women play a key role in seed and genetic resource conservation and in FSSa are recognized as active agents in maintaining the ecology and economy of the small farming household. Through management , conservation and regeneration of seed, women command the agrarian production cycles and occupy a natural and real power of command in the agrarian community through FSSs. Corporate ideology of seed displaces women from her real material conditions of power and creates false ideologies of ‘women's empowerment’. The capitalist-industrial development displaces women from agrarian economy to ensure a source of cheap labor for factories. In countries like Bangladesh they are mostly used in the export oriented industrial sector.These are fundamental issues of women's empowerment. The so-called ‘standardization’ of the seeds displaces women from their natural position of power in the agrarian economy. Seed is, therefore, the most critical and primary concern of the women's movement and a determining factor in reorienting our vision and realization of feminine values of seed keeping.

Seed & IPR

The Farmers’ Seed System implies collective ownership of the community over seeds and genetic resources. This ownership is based on the collective moral foundation and is inseparable from traditions, community relations, and natural law. This is in contrast to individual rights to privatize seeds or the introduction and use of harmful invasive or genetically engineered inputs, such as GMOs, without any ethical or moral consideration. Destruction of FSS opens up scopes for biopiracy, the introduction of GMOs, patenting of seeds and other lifeforms.

Seed rights, therefore, can not be individual rights. Seed and genetic resources must be held as commons. Privatization of seed and genetic resources happens because of the ignorance of the role played by FSSs in agroecology and biodiversity. Seed laws are dictated by breeders and corporate bodies and inevitably destroy the biological foundation of communities in favor of private corporate profit and industrial manipulation of life and biological world. Breeders claiming private rights on seeds indeed intend to destroy FSSs, and replace the life world of farming communities with the corporate world of profit and genetic erosion.

The FMSs are threatened not only by the capitalist-industrial transformation of agriculture, but directly by international conventions and laws. These laws are based on the principle of privatization and ownership of individual or legal persons and stand in contrast to the ideals of commons and free access of farmers to the community seed systems. The Union for Protection of Plant Varieties (UPOV) convention encourages plant breeding and its related innovations through a sui-generis (of its kind) system of plant variety protection and imposes plant breeders rights over seed and genetic resources at a national level.

Transforming seeds into private property instantly prevents free flow of germplasms and planting material’s within a community. Seed laws prevent the marketing and sale of uncertified farmer-managed seed varieties, rendering in many cases farmers exchange of seed as illegal. This is a weird and paradoxical situation and literally limits the role of farmers in ensuring food and nutrition for the community. The FSSs are directly affected by the seed laws. The selling of seeds by small scale resource poor farmers is seen as ‘illegal’.

The UPOV and IPR laws are essentially corporate laws and designed to shatter and destroy whatever is still left of FSSs. They are legal instruments by private seed breeders and seed corporations to consolidate, target, and market proprietary seeds to poor small-scale farmers, displacing farmers seed systems that have historically built up the foundation of farming. As a result few large transnational seed corporations emerged who control the international seed market.

UPOV criteria have been developed for industrial seeds, thus excluding peasants andIndigenous Peoples’ seeds from marketing mechanisms. Moreover, the exceptions contained in the 1991 Act of the UPOV Convention concerning the respect of peasants’and Indigenous Peoples’ rights are optional and limited to private and non-commercial use of seeds. As a result, UPOV restricts peasants’ and Indigenous Peoples’ rights to re-sow, conserve, exchange and sell seeds that they have selected from varieties that are protected by intellectual property rights.

The conflict between FSSs and commercial seed systems is not at all a scientific debate but at the core is the resistance of the farming community against corporate attempts to destroy the biological foundation of life and human conditions for survival. Corporations are desperate to control seed and food systems, re-edit the genetic code and manipulate the biological language of life to break and cross transgenic barriers.

Farming communities are naturally critical of corporate science that are often based on lies, propaganda and advertisement. Obviously , the conflict is between humanity’s common survival strategy and the corporate lies and propaganda that dominate the seed and food chains. Farming communities have never been against science and technology, rather their approach has always been to integrate science, innovation and technology that could contribute to agrobiodiversity and capable of addressing the planetary concern of climatic disaster. Science, technology and innovation should also address the problem of transition from fossil-fuel based agro-economy, and food culture. Needless to mention, a transformation of industrial lifestyles to save the planet in this anthropocene era requires science and technology that also addresses ethical questions of responsibility to earth and systems of life. Our practical knowledge must remain oriented towards building up localized food production, using agroecological principles recognized by the international community as reflected in the United Nations High Level Panel of Experts on Food and Nutrition as well as by the FAO.

Seed, FSSs & Human Rights

It is now recognized that seeds are central to the realization of the human right to food and nutrition particularly in the current context of financialization of economy, blatant political, economic and ideological power of large transnational corporations

compounding major crises such as climatic disaster and rapid loss of biodiversity. Vulnerability at the level of food and nutritional securities is alarming. In the context of the post-COVID pandemic recovery there is a broad recognition of the urgent need to promote sustainable, healthy and just food systems. It is not possible unless seeds and FSSs are brought to the central stage of policy concerns and the seed questions are reframed by the lens of the international human rights regimes.

There may be some scopes to address seed and FSSs issues in international covenants such as the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). Based on peasants’ and Indigenous Peoples’ past, present and future contribution to developing and maintaining biodiversity for food and agriculture, the treaty recognizes communities rights over seeds (“farmers’ rights”), including the right to save, use, exchange and sell their seeds. Right to privatize seeds and genetic resources by design excludes the community’s rights to commons, so the treaty is paradoxical. Breeders are claiming monopoly over seeds while using materials that have been historically safeguarded by FSSs. However, the ITPGRFA further establishes states’ obligation to protect peasants’ and Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge, echoing the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) has further clarified that rural women’s rights to natural resources, including seeds, are fundamental human rights. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP) specifies that the right to seeds includes states’ obligation to support peasant seed systems. These are useful openings to farmers and community organizations to recourse the existing debates on the conflicts between privatization and the necessity to hold seeds and biodiversity as commons of humanity.

The expansion of “the legal and geographic scope of intellectual property rights, whether through the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties ofPlants [UPOV] or patents have enabled coercion, exploitation and control of corporations over seed and genetic resources. Standardization and homogeneity caused genetic erosion.

The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) requires states to put in place some form of intellectual property protection on plant varieties. Although it explicitly allows countries to develop systems that are adapted to local contexts (so-called sui generis systems), the seed industry and several governments have used TRIPS and/ or bilateral trade agreements as a catalyst to promote the UPOV system, which sets significant limitations to peasants’ and Indigenous Peoples’ rights and seed management practices.

The issue of seed ownership and control is closely tied to broader questions about the ownership and control of food systems. When corporations control the seeds, they also control the food that is produced from those seeds, which can have profound implications for issues like food security, nutrition, and the environment.

Many small-scale farmers around the world rely on FSSs to sustain their livelihoods and feed their communities. When these systems are undermined or destroyed, it can have devastating consequences for these farmers and their families.

The shift toward corporate control of seeds and genetic resources is often accompanied by a corresponding shift toward monoculture agriculture, which relies on a limited number of high-yield crops grown at large scale. This can lead to environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, and increased vulnerability to pests and disease.

While proponents of IPR argue that it incentivizes innovation and investment in plant breeding, critics argue that it actually stifles innovation and reinforces existing power dynamics in the food system. For example, small-scale farmers may be less able to afford the high cost of patented seeds and may be less likely to invest in research and development of their own seed varieties if they fear their work will be co-opted by large corporations.

The issue of seed control also has important geopolitical implications. As large seed companies have consolidated their power over the global seed market, they have often used this power to promote certain crops and farming methods that are better suited to the needs of wealthy countries and corporations, rather than the needs of small-scale farmers in developing countries.

Ultimately, the issue of seed ownership and control is not just a technical question of intellectual property law, but a deeply moral and political question about who has the right to shape our food systems and our relationship with the natural world. By framing the issue in terms of human rights and justice, we can begin to shift the conversation and prioritize the needs of small-scale farmers, marginalized communities, and the planet itself.