Nayakrishi as an Eco-feminist Practice sdf

Farida Akhter || Tuesday 23 January 2024 ||

Farida Akhter || Tuesday 23 January 2024 ||

Introduction

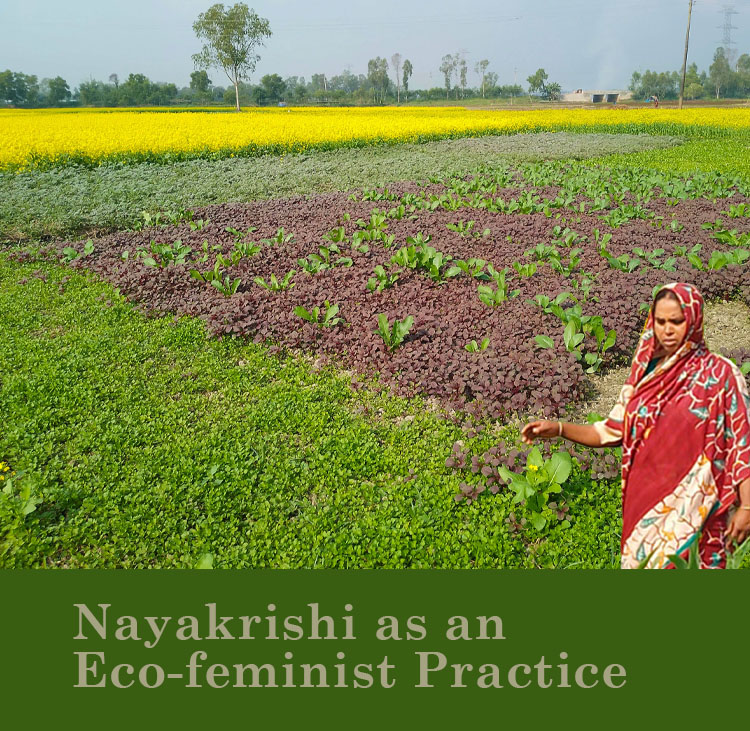

Nayakrishi, meaning ‘new agriculture, ' is a movement of small farming households in Bangladesh led by female farmers. The movement is critical for reducing food production into industrial fossil-fuel-based production systems driven by greed and denial of agriculture and rural lifestyle as a way of life. In the industrial paradigm of technology and production earth appears only as a source of raw materials and means of production and hardly the space where human beings share life with all life forms based on biodiverse relations and reciprocal dependence and/or caring. The characteristic feature of industrial civilization is not only the destruction of the planet Earth, as we are observing manifestly in climate disaster; from an agrarian perspective, we face the transformation of the rural landscapes into a huge dustbin or dumping ground of urban and industrial wastes. In Nayakrishi, agriculture is defined as a production system with no concept of ‘wastes’. Life is, by definition, the highest form of recycling and regenerating. This is the reason Nayakrishi Andolon is also known as ecofeminism in practice.

Avoiding all forms of destructive practices of industrial agriculture and building on life-affirming and cultural practices to co-evolve with nature is what Nayakrishi is about. Small and marginal farmers, owning less than a hectare of land, started Nayakrishi Andolon at a time when ‘krishi’ or agriculture only meant the cultivation of monocrop HYV variety “rice” and a few vegetables using seed packages with chemical fertilizers and pesticides. This was named ‘modern’ agriculture, approved by the elites and bureaucrats of the country, and governments took all measures to impose the practice on the farmers. Farmers who did not adopt were considered ‘backward’, and those who adopted were given incentives. Modern farmers received free or subsidized inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation facilities. However, farmers, particularly women in farming households, felt that modern agriculture invaded their sovereign right to decide what and how to produce. Unlike men, women felt the disempowering effect of modern agricultural technology since external technological intervention directly intended to replace the agrarian knowledge practices in which women had historically played a determining role in seed collection, conservation, management, and regeneration. Women felt the disappearance of the local varieties as losing their world. The loss of seeds and their replacement with industrial inputs is femicide and the destruction of the regenerative power, command, and glory of women.

Under modern agriculture, claims of increased yield on a few staples did not compare with the amount and cost of inputs and energy expended in production. Even the yield is not as high in the farmers’ field compared to the yield obtained in experimental stations, and it was justified in the name of ‘yield gap’; farmers were blamed for this failure because of their ‘ignorance’ and lack of scientific knowledge. In addition, there is a severe erosion of agro-biodiversity and no mechanisms to cope with the loss of genetic resources. Socially, poor and marginal farmers were on the verge of changing occupations as they could not purchase chemical inputs. Farmers faced a severe lack of sponsorship for growing traditional varieties. Using chemicals and pesticides in at least 40% of the farmers' fields had environmental spillover effects. Pesticides killed birds, and fish, and poisoned aquatic species, plants, and shrubs, even in fields where these were not directly used .

In the 1990s, farmers' responses to the negative impact of modern agriculture became pronounced. After experiencing severe floods in 1987 and 1988, the farmers couldn't cope with the loss of standing crops. In a desperate situation, the poor farmers sought an alternative to 'modern' agriculture. At the global level, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992, the concept of biodiversity made some inroads in the policy environment and allowed the farmers to experiment differently. It was also when UBINIG intensified the process of mobilizing the farmers for biodiversity-based farming, incorporating the local & indigenous knowledge of farmers, particularly of women. This approach involves newer knowledge of ecology, environment, and related national, regional, and international perspectives on biodiversity.

In Nayakrishi Andolon, the knowledge practices of the farmers are not taken in a ‘static’ sense or an ahistorical sense, as the term ‘traditional’ or ‘natural’ often means. It does not compromise the ethical and life-affirming principles of dealing with nature or the so-called external world of which communities are an integral part. Farmers practice 10 simple rules of biodiversity-based ecological agriculture to achieve a joyful, prosperous, and secure life, particularly sovereignty over food, seed, and knowledge practices. In addition to well-known ecological agriculture practices, Nayakrishi practice is based on biodiversity and the genetic resources in general and agro-biodiversity in particular as the strategic site to enhance agricultural performance. Nayakrishi attempts to design households, villages, and unions as ecological production systems at various levels and scales . It is a New Agricultural Movement, but at the same time, it is a living struggle of farmers to protect and enhance biodiversity and attain seed and food sovereignty.

Environmental pollution and ecological destruction caused a major change in rural livelihood, increasing and intensifying poverty. Farmers aggressively used chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation technologies for higher yields. In case of failures of the increase in yield, the blame was on the farmers for not using pesticides and fertilizer in the right proportions.

Modern agriculture, also known as the ‘Green Revolution’, reduced local varieties' cultivation without government support. It also caused agricultural knowledge and practice de-skilling that have evolved for hundreds of years. The dominance of the single plant paradigm of the ‘green revolution’ has systematically misguided the government in taking appropriate policies to enhance the yield. The genetic diversity of rice disappeared from the farmer’s field.

For Nayakrishi farmers, the immediate questions were how to eliminate the dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides as they could no longer bear the cost of fertilizers. They were in debt or had to sell land and change occupations. However, the main objective of the farmers was to increase the systemic yield of the agrarian systems. In this context, Nayakrishi primarily responded to the demands of small-scale and marginal farmers, who were hard-hit economically and ecologically by the so-called chemical-based modern agriculture. Nayakrishi offered farmers a way out from the package of HYV seeds and chemical fertilizer-pesticide-irrigation and enhanced agricultural performance.

The situation became so compelling that the farmers needed to buy more fertilizers at a higher price to maintain the same productivity levels. The fertilizer distribution system shifted from public to private, making it harder for the poor farmers to continue with agricultural cultivation. Until the late 1970s, fertilizer procurement and distribution was only through the public corporation called Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC), but due to pressure from the World Bank for reforms in agriculture; the system was changed towards the private sector and an unsubsidized system in early 1990s. In the early to mid-eighties, subsidies on inputs were cut back and domestic trading on inputs was liberalized.

Under the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the World Bank and IMF, Bangladesh was forced to reduce the support it had provided to the poor farmers. In the mid-nineties, the input market was liberalized, and later under the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), of the World Trade Organization (WTO) the output market was liberalized allowing the import of food items. That means, on the one hand, the input prices were higher in the competitive market and on the other hand, the price of crops was lower in the face of competition from outside from the countries who were continuing the subsidy to their agricultural production .

The 10 simple rules of Nayakrishi offered alternatives to chemical fertilizer, such as compost making and for pest management mixed cropping. But as the farmers became active, it became clear that the issue was not only giving up costly chemical fertilizers and switching to free compost. It was an issue of the kind of seeds that were going to be used for cultivation. The requirement of seeds for different crops is about one million tons, out of which only 18-20 percent is coming from the formal seed sector. The rest are coming from the farmers' own collection. About 70% of farm families are small, and they act as the key players in maintaining crop diversity at rural level.

Reduction in the number of farmers

Although the farmers constitute most of the population, the number is gradually reducing. During 1983–84, the contribution of agriculture was 49 percent of the GDP compared to only 10 percent for the industrial sector, and 18 percent for trade and transport. The gradual reduction in the agriculture sector's contribution to the GDP has been visible since 1990, with a 38 percent contribution to the national GDP. Currently, it contributes only 14.23 percent to the country’s GDP but employs 41 percent of the labour force. More than 55% of the total surface area is used for agriculture and 58% of holdings are in farming occupations. The small-scale farmers (holding land between 0.05 – 2.49 acres) comprise 84.27% of the total farming community. The result of the Green Revolution was not only in the erosion of genetic resources but also contributed to the reduction in the population engaged in agriculture. " As a major occupation of the population of Bangladesh, the census of 1961 shows that the number of people depending on agriculture was 86% (with 85% men and 91.8% women) while in the census of 2001 the number of people depending on agriculture reduced drastically to 50.9% (with 52.2% men and 43.9% women) . Even now, it is the small farm households, which have kept agriculture as a major occupation and continue to produce food for the country. However, in the post-independence period, farmers depended on chemical-based seeds supplied by the government. All the support to the agricultural sector was given only to crops identified by the government and to chemical-based ‘modern’ or mechanized agriculture.

Seed as a feminist site

Seed is the site where life is conserved and reproduced. While political sovereignty is related only to the political realm, the command, and control over seed include domination over the very life process itself and can not be left to the whims of the market or the Corporations. Asserting the farmer’s sovereignty over seed is the most contested site, not only to defend agriculture from environmental and ecological destruction but also to protect the very process of life without which we can not exist. Governments talk about the country's sovereignty in a narrow sense of political power. However, the state decisions on anti-farmer agricultural policy and undertakings of steps to destroy the ecology and the environment in support of the profit-oriented ventures of corporations have become a contested issue. Bangladeshi farmers’ sovereignty is threatened by the support of the government and international organizations for the introduction of corporate-based seeds. Nayakrishi farmers have been resisting those efforts and reconfiguring the meaning of sovereignty by which the State must protect, conserve, and reproduce life and the life processes without standing against the ecological culture of the farming communities. Thus seed sovereignty is directly linked with national sovereignty.

Seed sovereignty is not only a national issue but global. It implies the resistance of the agrarian civilization against the industrialization of life and nature. To win in this war, Nayakrishi farmers must forge alliances with farming communities worldwide with the same life-affirming objectives and goals.

It was ironic that new laboratory varieties of paddy were introduced when Bangladesh was already enjoying at least 15,000 varieties of paddy. All the 15,000 varieties of paddy that the farmers preserved over hundreds of years had particular names with very concrete descriptions of their qualities. Their productivity performance in different agro-ecological conditions was also varied including high yield performances. The names were interesting and very intimate to the farming families. They named the paddy as they name their children. The names of paddy are chamara, tulshimala, aloimalati, badshabhog etc. The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and its Bangladeshi counterpart, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), introduced HYV seeds. The names of the new varieties retained their abstract laboratory origin, such as BR-20, BR-11, BR-50 etc. One can see that it is far from farmers' perceptions of names. The practice of modern agriculture, especially through the promotion of fewer varieties of paddy has resulted in the erosion of local varieties to a large extent and narrowed the genetic base of agriculture. Farmers were persuaded to cultivate the so-called "higher yielding varieties" and not the local varieties which were considered as lower yielding. However, the HYV seeds available from the market undermined women's role in seed preservation.

Nayakrishi Andolon developed an effective approach that squarely lies in conserving, managing, and using local seed and genetic resources and adopting and improving production techniques suitable for farmers' seed in a diverse ecological environment. Hundreds of local varieties of rice, vegetables, fruit, timber crops etc., have been reintroduced quickly. For example, farmers in the Nayakrishi area regenerated at least 2800 rice varieties in the three seasons of Aus, Aman and Boro. These are collected in the three Community Seed Wealth centers and 19 Seed Huts in the three agroecological zones of Bangladesh. They also cultivate hundreds of different varieties of vegetables, pulses, oil seeds, fruits, spices, and timber and also preserve various plants, herbs, and aquatic plants that are useful as food, fodder, and medicine.

Among the 300,000 practicing Nayakrishi farming households, women are the key animators within and between households and are natural leaders of the movement, simply because the seed is the strategic site where women can assert their control and command in the production processes and cycles. It is the site of power, more authentic and direct, and ensures the position of women within rural Bangladesh. As a strategic site of action, seeds and genetic resources not only ensure biodiversity-based ecological production processes continue and expand, but control over seeds by women is necessary to constitute, retain, defend, and consolidate the power of women. In trade liberalization, WTO, and trade agreements, IPR regimes, particularly the Trade Related Aspect of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), seed is a political issue for women.

“Sisters keep seeds in your hands”

‘Sisters, keep seeds in your hand’ is the most popular mobilizing slogan of the farmer women. Nayakrishi Andolon is indeed a women’s movement. Women organize themselves through a very innovative seed network called the Nayakrishi Seed Network (NSN). The responsibility of the NSN is to ensure the collection, conservation, distribution, and enhancement of seeds/germplasm among the members, primarily women. The Nayakrishi Seed Network (NSN) builds on farming households, the focal point for in-situ and ex-situ conservation. Farmers maintain diversity in the field but at the same time conserve seed in their homes for several years to be replanted in the coming seasons. Usually, the seeds that are kept for longer periods generally have lower germination rates. Still, the technology farmers use to preserve these seeds is varied and effective, both for short and long periods.

This is where farming women assert their role and power and is the basis upon which Nayakrishi Seed Network (NSN) has been built. The individual plans and decisions are made into collective decisions through meetings and collective information sharing. Decisions are taken to ensure that in every planting season, all the available varieties at the farmer's households are replanted and the seeds are collected and conserved for the next season.

A Specialized Women Seed Network (SWSN) is formed within the NSN. The specialization encourages women to be more focused individually on a few species/varieties, and as a result, they develop valuable knowledge in a particular variety. Since the group highly values this knowledge, the person gets immense respect and recognition, contributing to the collective spirit and knowledge sharing. They also monitor and document the introduction of a variety in a village or locality. They keep the information about the variability of species for which they are assigned. The SWSN members often share information in large meetings.

Community Seed Wealth (CSW) center is the institutional setup in the village that ensures the collection and conservation of seeds germplasm of the respective areas. Any member of the Nayakrishi Andolon can collect seed from CSW with the promise that they will deposit double the quantity they received after the harvest. The seeds are sold to other farmers of the village, and the CSW cost is maintained from the income. Farmers can claim the deposited species or a variety at any time. All they need is to walk to the nearest CSWs. A farming household can decide not to replant a species or a variety in a season but may return after two to three years for the same.

Women’s Knowledge of Seeds

Women were and still are very confident about their knowledge and role in seed preservation. This is found among the Nayakrishi farmer women. They exactly know all the characteristics, even of those, which are endangered and not grown in the area anymore. In a small research on women’s knowledge and practice of seeds in four areas, the information received from women (2006) showed that women know the seeds a. which are available locally, b. which are cultivated in the field, c. which are introduced from outside (including HYV and Hybrid) and d. those that are disappearing or have disappeared from their area. For example, they gave information about 52 rice varieties that were to their knowledge not grown there anymore, compared to 35 varieties grown in the field and 21 HYV-introduced varieties. For vegetables, they had knowledge about 73 different vegetable varieties not grown anymore and 49 different vegetable varieties grown and introduced in the area. That is, more seeds are in the knowledge of women and much less about the introduced ones, as they do not preserve those seeds. They call seeds in their memory and knowledge as ‘Gayner Beez or Seeds of Knowledge. It is amazing to see the level of confidence among women about the seeds that are in the knowledge of women.  Many women could exactly describe the seeds they named and even say whether they had seen them in the last ten to fifteen years. Most seeds categorized as seeds of knowledge were apprehended to be lost in that area during the last ten years. However, women had much confidence that the seed must be available in another area, maybe in another name.

Many women could exactly describe the seeds they named and even say whether they had seen them in the last ten to fifteen years. Most seeds categorized as seeds of knowledge were apprehended to be lost in that area during the last ten years. However, women had much confidence that the seed must be available in another area, maybe in another name.

If there is a name of seed, then the seed exists somewhere. If it is not found in our village, it must be available elsewhere’ -- Farmer Rabeya, Tangail

Women were also confident that the seeds that are in their knowledge can be identified by them if they see those seeds among thousands of other seeds. Farmer Rabeya said,

‘The seeds are like children, we can find them from anywhere they are available’

In a workshop held in Tangail from January 30 – 31, 2006 this practice was done for seeds of knowledge. Some could find the endangered seeds in the Community Seed Wealth Centre. This was a very interesting exercise where a lot of seeds that were identified as seeds of knowledge in one area were categorized as local seeds in another area. The farmers felt that the seeds were not lost at a time from all the areas. The loss was a gradual process and mostly happened after natural disasters. They lost the preserved seeds and then got seeds from outside or a different market.

Women could name certain varieties of potato, which they thought had been lost over 40 years. The older woman gave this information. Mallika Begum of Bag Hasla village said:

We had several potato varieties such as Kukri, Khetor, Surjo mukhi, etc. We do not see these potatoes anymore.

It was very clear from the discussions that the major causes of the loss of seeds were the introduction of HYV and Hybrid seeds. Women distanced themselves from such acts.

‘We have never bought hybrid seeds from the market. But our husbands did. And then they bought the chemicals and destroyed everything’

Mallika Begum, Baghasla, Ishwardi

The cash crops such as local sugarcane were lost. These local variety sugarcanes had beautiful names, such as Mershi dana, Gendari, etc. Many of these local variety sugar canes were eaten raw which are soft and sweet. They made molasses in their own homes. A sugar cane named ‘Akhash Dhor-dhor’; ‘Akash Dhor’ meant touching the sky. That means the sugar cane was high enough to look like catching the sky. It was one of the favorite sugarcane varieties in Pabna and Kushtia areas. Once the Sugar Mills started controlling production these varieties were not produced anymore.

Struggle against Hybrid Seeds

Most introduced vegetables such as cauliflower, potato, cabbage, tomato, chili, etc. are either HYV or hybrid. Farmers familiar with HYV varieties of rice know the differences in cultivation practices between the local and HYV varieties. They know about their performances and already had many negative experiences. Both HYV and hybrid claimed higher productivity. But soon the differences between HYV and Hybrid became clear that with Hybrid seeds, farmers cannot save the seeds for the next crop; they must purchase from the market.

The promotion of hybrid rice happened initially through two processes: a. Import of Hybrid Rice seeds through the private sector and b—development of Hybrid Rice through Government Research Institutes. Hybrid rice seeds were, therefore, more known as imported seeds. Besides the Traders, NGOs (such as BRAC, Proshika, ASA) working with the poor offering micro-credit became the agents of hybrid seed importers. At the government level, research and introduction of any new variety of rice is the responsibility of the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI).

IRRI has initiated a project from 1999-2000 to introduce hybrid seeds through Poverty Alleviation organizations. Poverty Elimination through Rice Research Assistance (PETRRA) was a 9.5m GBP five-year project (1999 – 2004) funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and managed by the International Rice Research Institute, in close partnership with the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), and Ministry of Agriculture. They targeted the poor rice farmers to accept hybrid rice seeds. Women are particularly targeted as they are major recipients of microcredit programmes. NGOs involved in PETTRA were BRAC, CARE, Grameen Krishi Foundation (GKF), and Proshika --- all of them are known for using micro-credit to push the hybrid seeds to the clients.

Struggle against GMOs: The Golden Rice and Bt Brinjal

The Nayakrishi farmers oppose GMOs because these directly threaten their present practices and interests, without offering any agronomic value. Farmers have already demonstrated a better way to enhance both productivity and agro-biodiversity.

The corporate effort to introduce Golden Rice, the genetically modified rice enriched with Vitamin A is seen as an assault on the ongoing experiments, innovations, and successes of the peasants. There is no support from the government for ecological agriculture and hardly any environmental and ecological concerns meaningful to the farmers. The bio-safety regimes are absent and there is an alarming lack of awareness about the ‘precautionary principle’ among the scientists. The Nayakrishi farmers have rejected the promoters' claim that Golden Rice will solve the problem of Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD). They are confronting Golden Rice and all the propaganda around it as an invasion against the farmers’ efforts to ensure food and seed sovereignty. The desperate corporate trickery to claim that Golden Rice is a ‘gift’ to the people of Bangladesh has also been exposed.

To the peasants, GMOS are ‘bikrito’ entities – which is not natural, absurd, degenerated and potentially harmful. For Nayakrishi farmers ‘Golden Rice’ is known as ‘bikrito dhan’ – an unnatural and absurd variety of rice. Any sane human being never mutilates a natural entity but rather appropriates nature's evolutionary power in maintaining the integrity and unity of the evolutionary product. In a country rich in cultural and linguistic metaphor, the term ‘bikrito” has a very strong connotation in the Bangla language and can never be captured by terms such as ‘genetic engineering’. Peasants are for constant innovation and discovery. By making ‘bikrito dhan’ through a distinctly different type of absurd operation, the innovative capacities of humankind are compromised. Farmers argue that Golden Rice is not an innovation but a product of pathological corporate projects that intend to replace natural forces with ‘experimental laboratory’ operations controlled by corporations. A person is insane (‘bikrito mostishko’) implies that he/she no longer can cope with reality and is trapped in the glasshouse of his/her own mind. This is what the ‘bikrito’ scientists are toying with ‘bikrito dhan’ with corporate support. This is very important to recognize the vocabulary through which farming communities are resisting the corporate propaganda.

Vitamin-A in food is found as retinol or as Carotene. Retinol is found exclusively in animal foods including eggs, milk, animal and fish livers and fish oil. Carotenoids are found particularly in plant foods, including vegetable oil, dark green leafy vegetables, algae, red/yellow vegetables, and tubers, and red, orange fruits, flowers, and juices. Several successful programs to improve vitamin-A status with food interventions have been reported.

Improvement in the condition of night blindness in Bangladesh was done by conducting nutrition education among patients so that more vegetables and fruits (rich in vitamin-A) and oil were incorporated in the children’s diets. Mango and Papaya, the most common fruits, are rich in vitamin-A.

The Nayakrishi Farmers have characterized indigenous rice germplasm collected from all over the country according to their nutritional quality. They have found 80 accessions to have vitamin A. Rice husked by the local implement, Dheki contains higher amounts of vitamin A. To hold vitamin A in the cooked grain, the cooking method should be such that the water after cooking should be absorbed by the grain.

Uncultivated foods such as leafy greens, tubers, small fish, and small animals collected from agricultural fields, water bodies, and forest areas constitute nearly 40% of the diet in the communities where local biodiversity has been conserved. Most of the items are potential sources of vitamin A . The leaves of Corchorus capsularis contain a bitter glycoside, corchorin and taste bitter on chewing, hence, it is known in Bangladesh and India as ‘Tita (bitter) pat (Jute), whereas the almost tasteless leaves of Corchorus olitorius are referred to as ‘Mitha’ (sweet) pat. The leaves are an important source of beta carotene, the precursor of vitamin-A. In general, the consumption of leafy vegetables in the tropics is far from optimal, particularly concerning that the vitamin-A requirement in such regions frequently depends on vegetables products, and especially on leaf sources.

Bt Brinjal

Bangladesh has been a target country for the Bt brinjal under the Agricultural Biotechnology Support Project (ABSP II) and the 'Monsanto technology' - a joint venture with Maharashtra Hybrid Seed Company (Mahyco), India and its collaboration with the private seed company East West Seeds, Bangladesh. Mahyco transferred the technology and basic breeding material of Bt brinjal to two Indian public sector institutions (PSIs), the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore (TNAU) and the University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad (UASD), though the ownership of the GE event EE-1 still rests with Mahyco. The Bt brinjal contains a gene construct of Cry 1 Ac from Monsanto, the American MNC. The PSIs will use the Mahyco material to backcross with their brinjal varieties to incorporate the genetic event into them, imparting tolerance to the fruit and stem borers of brinjal that cause severe damage to the produce.

This partnership arrangement was extended to the Indian Institute of Vegetable Research, Varanasi, University of Philippines in Los Banos, a government research institute, Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), and a private seed company, East West Seeds, Bangladesh. The Agricultural Biotechnology Support Project II (ABSP II) funded by USAID and led by Cornell University aimed to provide substantial benefits from agricultural biotechnology to countries in East and West Africa, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines. The Bt Brinjal is a piracy of the local variety brinjals to be genetically modified for patenting by the Monsanto-Mahyco partnership.

BARI has been conducting field trials of Bt Brinjal with an MOU with Mahyco starting in 2006. Bangladesh's government is a signatory of the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, which is the first international agreement to regulate the transboundary movements of genetically engineered (GE) organisms. The Biosafety Protocol is a subsidiary agreement to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), signed by over 150 governments at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the Protocol itself was agreed in Montreal in January 2000 and came into force September 11, 2003. Following the protocol's obligation, the Bangladesh government formulated the Biosafety Guidelines for Bangladesh by the Ministry of Science and Technology in 2005, which was earlier formulated in 1999. Considering the obligation of the said protocol, the guidelines have been updated by the initiative of the Ministry of Environment and Forest, MOEF has also considered National Policy on Biotechnology and recast various aspects of Risk Assessment and Risk Management in the light of the Cartegena Protocol. The Biosafety Protocol is an agreement designed to regulate the international trade, handling and use of any genetically engineered organism that may have adverse effects on the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health.

According to the Biosafety Guidelines of Bangladesh, consideration needs to be given to ensure that the introduction of GMO/LMO does not interfere with the protection of genetic resources and biological diversity.

Bangladesh is among the few known as the country of origin of brinjals. There are many different varieties of brinjals in the country and farmers are growing those brinjals in different agro-ecological zones. However, Bt Brinjal field cultivation was approved by the Ministry of Environment, bypassing the Cartegena protocol requirements. The introduction of the Bt Brinjal has posed a threat to the genetic diversity of brinjals and will assert monopoly control of genetic resources by multinational companies by destroying the sovereign rights of farmers over the seeds. This is not acceptable. We do not need Bt Brinjal, as we have many varieties. Farmers dd not accept the seeds given by the Department of Agriculture and this project has failed so far.

Conclusion

Nayakrishi Andolon’s championing of ecological agriculture resonates deeply with feminist principles, offering a path towards food sovereignty, biodiversity conservation, and social justice. Exploring the convergence of these two seemingly disparate realms, highlighting how ecological agriculture empowers women and aligns with feminist goals, is fairly obvious.

Feminist Principles:

Feminism, practiced in strengthening democratic polity, encompasses a spectrum of ideologies advocating for gender equality and women's rights. Key principles relevant to Nayakrishi’s ecological agriculture include

- Equality and empowerment: Nayakrishi Challenges systemic inequalities that disadvantage women, including unequal access to land, resources, and decision-making power.

- Sustainability and care: Recognizing the interconnectedness of all living beings and advocating for practices that preserve the environment for future generations.

- Self-preserving bodily autonomy & self-determination:` Women's right to control their bodies, resources, and livelihoods, including their choices in agriculture and food production. Nature from a feminist perspective appears as the extended body of human beings.

- Knowledge sharing and collective action: Recognizing the value of indigenous knowledge and women's traditional practices, while fostering collaboration and community resilience.

Nayakrishi’s 10 Rules contains ecological agriculture principles and aligns with these feminist principles through its core values:

- Biodiversity & agro-ecology : Promoting diverse ecosystems that mimic natural systems, fostering resilience and providing habitat for a variety of species. Utilizing natural methods like composting, crop rotation, and intercropping to maintain soil health and reduce reliance on harmful chemicals.

- Food, seed, and nutritional sovereignty: Supporting local food production and systems based on local seeds prioritizing community needs and nutritional security, particularly for marginalized groups like women. Preservation and exchange of diverse, locally adapted seeds, challenging corporate control over seeds also defends the bio-geographical foundation of agriculture. and promoting farmers' independence.

- Fairness and equity: Creating a more equitable agricultural system that empowers small-scale farmers, often women, and promotes fair distribution of resources and benefits by resisting corporate control of agriculture and instability of the market.

- Intergenerational responsibility: Protecting the environment and agricultural resources for future generations, ensuring long-term sustainability and food security.

- Women's leadership: Empowering women through training, knowledge sharing, and collective action, enabling them to participate actively in decision-making and leadership roles within the movement.

1. Corporate promotion of Hybrid Rice in Bangladesh by UBINIG, n.d.

2. Ten Rules are: (1) absolutely no use of pesticide (2) in situ and ex situ conservation of seed and genetic resources, (3) production of healthy soil without external inputs, particularly chemical fertilizer, (4) Mixed cropping (5) production and management of both cultivated and uncultivated spaces (6) no extraction of ground water and conservation of water and efficient surface water use and management (7) learning to calculate the output both in terms of single species and varieties as well as system yield (8) Integrating livestock in the household to produce more complex household ecology to maximize benefits and well being of both humans and life forms (9) Integrating water and aquatic diversity to generate more ecological products and (10) integrating non-agricultural rural activities to ensure prosperity of the local communities as a whole.

3. Nayakrishi Experience: Addressing food crisis through biodiversity-based ecological production Systems by Farhad Mazhar Presented at Policy Dialogue series on 8 July, 2008 organised by UNDP, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4. Agriculture subsidies: Govt. Pledges vs IFI’s aversion; IFI Watch, Bangladesh, Issue # 1, Year 6, January 2009

5. Mazhar, F. 2009. Agriculture in Copenhagen COP 15; nothing to expect but much to do by the bio-diversity-based ecological practices.

6. Statistical Pocket Book Bangladesh 2010, BBS, GOB, February 2011

7. Farm holdings are divided into three categories: small, medium and large. A small farm holding has an operated area between 0.05 and 2.49 acres of land while a medium farm holding has it between 2.50 and 7.49 acres. A large farm holding is one having an operated area of 7.50 acres or above.

8. Population Census 2001 National Report (provisional) Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Planning Division, Ministry of Planning July 2003

9. Defending the integrity of Life and Diversity in Seeds of Movement by Farida Akhter, 2012

10 Women’s Knowledge and practice in seed by UBINIG, 2006

11. Kuhnlein H.V. and Gretel H. Pelto 1997 ‘Culture, Environment, and Food to Prevent Vitamin A Deficiency’ International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries (INFDC) and International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada, P.205

12. Uncultivated food; The missing link in livelihood and poverty programme, The South Asian Network on Food, Ecology and Culture, Policy Brief, 1: 11 November 2004

13. Denton, I.R. Vegetable Jute (Corchorus), Jute and Jute Fabrics, Bangladesh. 19 (9) : 7-12. 1998